________________________________________________

RA Kris Millegan©2000

![]()

________________________________________________

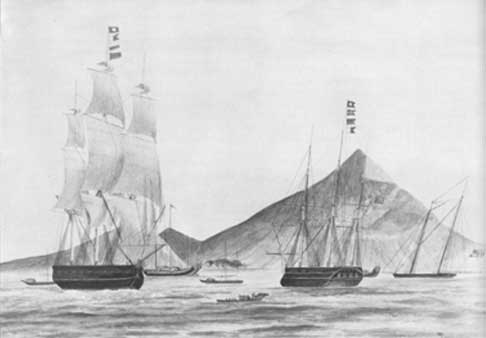

The Charmer, China Trade Clipper Ship launched 1854

The Charmer was built in Newburyport, Massachusetts by Geo. W. Jackman for Bush & Wildes of Boston.

Hon’ble John’s Band

"When we sold the Heathen nations rum and opium in rolls,

And the Missionaries went along to save their sinful souls."

The Old Clipper Days

--Julian S. Cutler

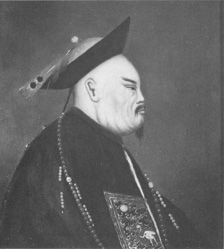

Col. WH Russell in his later years

William H. Russell (Skull &Bones; co-founder-1833) cousin Samuel Russell formally established Russell & Co. on January 1, 1824 for the purpose of acquiring opium and smuggling it to China. Russell & Co. merged with the number one US trader, the J. & T.H. Perkins "Boston Concern" in 1829. By the mid-1830s the opium trade had become "the largest commerce of its time in any single commodity, anywhere in the world." Russell & Co. and the Scotch firm Jardine-Matheson, then the world's largest opium dealer working together were known as the "Combination." George HW Bush (S&B 1948) was born in Milton, Massachusetts not far from the historic home of Robert Bennett Forbes, a Russell partner. Many great American, European and Chinese family fortunes were built on the "China"(opium) trade. Yes, they sold porcelain, tea, silks and other items at home in the US, but they "needed" the trade in opium for silver to pay for the desired goods and—opium smuggling returned "handsome" profits

Samuel Russell of Middleton, Connecticut

Opium smuggling didn’t just make money. At times, opium was money. Opium built empires and had a hand in financing much of the world’s infrastructure.

Wrapper for opium packet. Singapore c.1920

From Carl A Trocki’s excellent book, Opium, Empire and the Global Economy(1999):

"The trade in such drugs usually results in some form of monopoly which not only centralizes the drug traffic, but also restructures much of the affiliated social and economic terrain in the process. In particular two major effects are the creation of mass markets and the generation of enormous, in fact unprecedented, cash flows. The existence of monopoly results in the concentrated accumulation of vast pools of wealth. The accumulations of wealth created by a succession of historic drug trades have been among the primary foundations of global capitalism and the modern nation-state itself. Indeed, it may be argued that the entire rise of the west, from 1500 to 1900, depended on a series of drug trades."

<>

". . . the image of the "opium empire," a metaphor first offered by Joseph Conrad. It takes up the early history of opium and other "traditional drugs" such as tobacco and sugar and develops the paradigm of commercialized drug trades and ties that to the growth of European colonialism in the Americas and Asia . . ."

<>

". . . links between drug trades, European colonial expansion, the creation of the global capitalist system and the creation of the modern state. Drug trades destabilized existing societies not merely because they destroyed individual human beings but also, and perhaps more importantly, because they have the power to undercut the existing political economy of any state. They have created new forms of capital; and they have redistributed wealth in radically new ways."

<>

"Opium thus created a succession of new political and economic orders in Asia during the past two centuries. These included the state of the East India Company itself, the new Malay polities of island Southeast Asia, the colonial states of nineteenth-century Southeast Asia and the warlord regimes of post-Qing China as well as the Guomindang and communist states that arose out of that milieu. At the same time, the economies of the entire region were radically reoriented, or perhaps "re-occidented" would be a more appropriate word. India's opium production was brought under western control while China's domestic economy was opened to the west. Southeast Asia was first opened to western traders and then to western control. With the migration of Chinese labor, Southeast Asian economies were transformed into commodity-producing regimes focused on exporting to the industrializing western Powers. Underlying all of this, opium rearranged the domestic economies and pushed them down the path of mass consumption, which together with mass production, typified the "modern" economic order.

It is possible to suggest a hypothesis that mass consumption, as it exists in modern society, began with drug addiction. And, beyond that, addiction began with a drug-as-commodity. Something was necessary to prime the pump, as it were, to initiate the cycles of production, consumption and accumulation that we identify with capitalism. Opium was the catalyst of the consumer market, the money economy and even of capitalist production itself in nineteenth-century Asia.

<>

Opium was the tool of the capitalist classes in transforming the peasantry and in monetizing their subsistence lifestyles. Opium created pools of capital and fed the institutions that accumulated it: the banking and financial systems, the insurance systems and the transportation and information infrastructures. Those structures and that economy have, in large part, been inherited by the successor nations of the region today."

One might say, whomever controls opium—controls . . .

And it is especially profitable when its illegal, plus the corrupting side-effects that can be "played" towards . . .

The Opium Poppy

O just, subtle, and all-conquering opium!

--Thomas De Quincey

Confessions of an English Opium-Eater

Who first discovered the opium poppy’s attributes is lost in the depths of time. Research suggests that "there are no truly wild" opium poppies and all extant species are cultivars. Opium poppy’s "genetic alterations"—along with a just few other drug and food plants—"imply that the plant is the product of an extensive and sophisticated process of primitive genetic engineering." The basic litany of opium’s history is that cultivated opium seeds and pods have been found at Neolithic sites in central Europe from the fourth millennia B.C. and the plant spread to the south and southeast. Over 5000 years ago, Sumerians were growing opium poppies—the "joy plant"— for both its medicinal and "narcotic" properties. The Assyrians—who called it "lion fat"—assimilated opium use from the Sumerians. The Assyrians passed its use on to the Babylonians, who engendered opium use among the Egyptians. Here use flowered with a unique "thebiacum" strain being developed. A strain with a high amount of thebaine—one of opium's 24 alkaloids—very medicinal but not as soporific. Many classical Egyptian royal tombs were "decorated with paintings of opium poppies" among other medicinal plants. Ancient Egyptian texts included an opiate preparation "Remedy to Prevent the Excessive Crying of Children"—a use carried through many cultures up through the patent medicines sold in America, Britain and elsewhere until the early 1900s. The Egyptians engaged in a strong trade with their strong medicinal variant throughout the Mediterranean.

From two Mediterranean isles, comes the only archeological evidence of the smoking of opium before the sixteenth century A.D. The "Peoples of the Sea" on Cyprus were smoking opium in ceramic pipes and were using slashing culling knives on opium pods before 1100 BC. From "primordial opium dens" and other sites on Crete, archaeologists have uncovered sophisticated smoking devices, very similar to ones devised by the Chinese 3,000 years later and—a most amazing statue.

"The Poppy Goddess, Patroness of Healing" is about three feet high with three poppies in the front of her tiara. Some "archeologists speculate that this female deity, crowned with poppy pods, presided over an opium-smoking cult on Crete over 3,5000 years ago."

The Greeks looked to opium as both a medicine and a magical talisman within their mythos—a "sacred plant to which were consecrated altars and priests." Then circa 600 B.C. the Greek culture began transforming from one of magic and myth to one encouraging reason and the study of knowledge. One of the big changes was from choosing of a pharmakos—a sacrificial human scapegoat, to be stoned to death—towards a cult of doctor-priests gathered around the legend of Aesuclapius. They were known to give their patients an admittance exam consisting of an opiated potion accompanied by sleep on a freshly-skinned rams skin. After the patients slept they were queried about their dreams for a prognosis and diagnosis. Hipocrates was born near the Aesuclapisian main hospital on the isle of Cos in 460 B.C. Hipocrates stripped away the magic to become the father of medicine. He showed opium to be "useful as a cathartic, hypnotic, narcotic and styptic" and bespoke of monitored moderate usage. The Aesuclapisians were the medical establishment all through the Roman era. The isle of Cos was a favorite rehabilitation clinic for Nero, who had been enthroned with help of another use of opium—a poison. His mother Agrippina put opium "in the wine of her fourteen year-old stepson, Britannicus." The dissolution of the Roman European empire into the Dark ages left it to the Crusaders to bring back to Europe familiarity of the drug and its uses from the Arabs.

"Healing" in medieval European took many forms, not all being medicinal. The all-powerful church declared that disease was demonic and exorcisms were prescribed. The Arab physicians, the midwives/herbalists and a classical-based school started by Muslim physicians at Salermo on Sicily were the ones that understood and used opium. The "kill-cure Frankish system"—one of leeches, bleeding, blistering, trepanning—"known in its time as Heroic medicine," (ironically some say the root of the word heroin) didn’t generally prescribe opium, decrying it as "lazy."

In the first part of the 1500s Theophrastus Bombastus von Hoheheim, otherwise know as Paraclesus created the famous opiated potion, laudanum. Laudanum has come to be a generic term for a variety of oral opiate preparations. When laudanum is made to Paraclesus’s original recipe using orange and lemon juice, one gets a primitive form of heroin. Laudanum-named preparations were a staple medicine used by medical doctors up through the early decades of the twentieth century. Although a tussle between herbalists and medical practitioners continued, the medical establishment embraced laudanum and other opiate preparations for pain relief and their effect of masking the symptoms of disease.

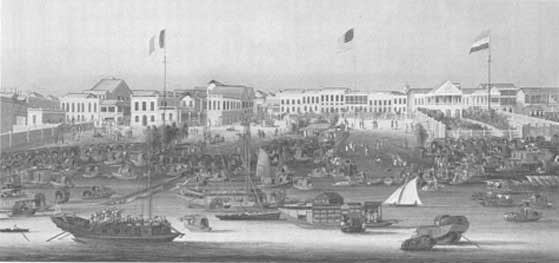

Foreign Factories at Canton 1830-1840, Sunqua

The Opium Trade

"If the trade is ever legalized, it will cease to be profitable from that time. The more difficulties that attend it, the better for you and us."

-- Directors of Jardine-Matheson

The Portuguese arrived in China in the early 1500s and after an abortive attempt to settle near latter-day Hong Kong they were permitted to establish a trading base at Macao in 1557. They brought the first European traded opium to China from their colony of Goa. Arab traders had been bringing in opium ever since around 400 A. D. There was already some domestic production for medicinal uses, opium poppies having reached China some 300 years earlier. The trade had become steady—mainly medicinal—about 200 chests a year until the advent of the Europeans. The era of royal-chartered mercantilist enterprises was afloat and as the Portuguese influence in the East began to wane—there was a rush to fill the void. The Dutch, English and French each began large "corporate" ventures into the "spice" trade. There was also trade interests by other European nations plus Russian, Armenian, Jewish, Parsee and American merchants.

The opium trade sparked when the smoking of opium was "introduced." Sailors in the tropics—some for a medicinal benefit against tropical maladies—began to mix opium with their tobacco in their pipes in the late 1500. This was picked up by various populations and developed into its own subculture. Soon there was the dropping of the mixing with tobacco to a prepared opium smoke(chandu). And special pipes—very similar to ones used on Crete several thousand of years earlier.

The Dutch began trading opium in the 1610s, and not just as a profitable trade item. They used opium "as a useful means for breaking the moral resistance of Indonesians who opposed the introduction of their[Dutch] semi-servile but immensely profitable plantation system." In 1689, the English began trading at Canton and by the early 1770's they surpassed the Portuguese, Dutch and French to "became the leading supplier" to China. Because the Spaniards were allies of the America during the US War of Independence and thus no Spanish silver was available to pay for Chinese tea, the British monopolized the source of opium (India) and became the major trafficker. Later, increased competition and the hard facts that a tenth of the British tax base came from tea—and the tea came from China—gave an impetus for an increase in production and reduction in price of opium in the 1820s. "In other words; so that the British public could go on drinking their millions of gallons of tea each year, twice as many Chinese opium addicts (and for that matter, British opium addicts) had to be created." At first, it was thought in China that the English were buying the tea and rhubarb in such large quantities because the Chinese believed the British to be a constipated race because of their dietary inclusion of milk products.

Many historians discount the American activity in the opium trade, generally concentrating on the British and their mercantilist trading syndicate, the British East India Company. Because of the Navigation Act of 1651, Americans "were not permitted to sail their own ships to the Orient," they were required as colonists and subjects to buy all their Chinese goods in London from the East India Company. The East India Company’s monopoly on the tea trade was more of a reason for the American Revolution than the cost of the tax. Through a political arrangement the tea was actually coming in for less than it could be bought in England. But the agitation of Samuel Adams, Ben Franklin and others had led to situation where ships were sent back to England unloaded, some cargoes rotted other shipments were destroyed—ala, the Boston Tea Party.

American smugglers, many of them prominent merchants, were already buying tea and Chinese merchandise from the Dutch and others. Smuggling was big business. The actual "tea tax" paid officially some years was very low in relation to tea that was drank. After the revolution, Americans were free to embark on their own mercantile adventures and when the East India Company outlawed their own ships from carrying opium, in 1805, American companies jumped right in. The War of 1812 caused some interruption of the trade but after the war the Americans held a major portion of the trade for many years.

The first US ship in the China Trade was the Boston sloop Harriet; it had traded American ginseng for Chinese tea. It didn't even get all they way to China, it traded its goods off the Cape of Good Hope. The Empress of China was especially built for the trade by Philadelphia's Robert Morris and first set sail towards China on Washington's birthday, February 22, 1784. It took ginseng and brought back teas, spices, silks, porcelains and other general household goods. There was interest in the products, a good profit was made and the China trade was off and running. Ginseng, seal and sea otter furs, and sandalwood were used to trade with the Chinese. Soon these resources were depleted and a new barter item was needed in lieu of silver—which the fledgling US had little of. In the late 1790's Smyrna (Izmer, today), Turkey a major source for opium began to become port of call for Americans.

Until 1792 part of the Perkins family shipping business, along with their Cabot relations was the slave trade. In 1789 Thomas H. Perkins first went to China with Elias Derby from Salem, Massachusetts. A "loyalist" cousin, who fled America during the War of Independence, George Perkins was a merchant in Symrna. With a solid "connection", a strong family framework and firm financial backing Perkins & Company became the leader in the American pack. It was a family affair. Thomas H. was brother-in-law of Russell Sturgis, an uncle to J.P. Cushing and brothers John M. and Robert B. Forbes. Joshua Bates, a partner in Baring Brothers Bank, handled the family business in London. He was married to a Sturgis. Russell Sturgis's grandson later became Chairman of the Board of Barings.

Perkins & Co. found that illegality both in nature and operation discouraged competition and used sporadic attempts by the Chinese Government to enforce their opium prohibition, "to [build] the machinery that allowed it to control the Canton market for Turkish opium." Perkins & Company became the first American firm to operate a "storeship" at Lintin in a new smuggling procedure. The opium was unloaded onto the "storeship," then the trading vessel would travel on to Canton with chits. The chits were then sold and the opium was retrieved later by the Chinese buyer. Smooth as silk—all illegal—but bribes were paid and business was good.

Samuel Russell and Phillip Ammidon came to Canton in 1824, Russell having first been there in 1818 as a business representative for a merchant house out of Providence R.I. Ammidon went on to India to serve as the firm's opium buyer. In "a series of accidents and coincidental decisions" Russell & Company acquired a "virtual" monopoly on the American portion of the trade in the 1830's. Other eastern merchants failed, died, or retired like John Jacob Astor. Perkins & Company, resident partner in Canton, Thomas T. Forbes was drown in August of 1829, and he carried a letter which gave Russell "charge of the firm's [Perkin's] business."

In the 1830's the price of opium went down and shipments of opium to China went up. The decade started out with four times the shipments of 1820 and by 1838 over ten times. The opium clipper—introduced by the Americans—with its ability to sail against the monsoons made three round-trip journeys within one year instead of taking up to two years. Profits were huge and there was a large flow of silver being introduced from China into booming western economies. In early 1837 there was a price-crash in the opium market and the speculators losses reverberated around the world in a financial panic in which specie became scarce both in Britain and the US.

August Belmont came to New York City in 1837, a stopover on his way to Havana, but stayed on in Gotham, buying securities, debts and property during the "Panic of 1837." Many say he was acting as an agent for the Rothschilds. Also in 1837 George Peabody, an old "China" trader—among other ventures—settled in London and brought into his sphere JS Morgan, progenitor of JP Morgan. Many Bonesmen were partners and principals in Morgan-related firms.

Robert Bennet Forbes (1804-1889) c. 1846

In Robert B. Forbes's autobiography Personal Reminiscences (1882), he talks about talking a trip to visit "constituents" in Europe, in 1841. His uncle, merchant T.H. Perkins went with him. In London they met with Forbes, Forbes and Co, Barings and the Rothschilds, "who were valuable constituents of Russell & Co."

That RB Forbes was obliged to go back to China to make another "opium" fortune—having lost his last because of financial problems brought about by the panic—is to say the least— ironic.

The "Combination", Russell & Company and the Scotch firm Jardine-Matheson, the largest opium trader, together developed a new trade up and down the China coast—the romantic opium clipper—and helped to spread the use of the opium further in China. After the first "Opium War" Russell & Co. became the third largest dealer in opium in the world.

RB Forbes spent many years at the opium smuggling station off Lintin Island c. 1830s Anon.

British engaging the Chinese January 1841

The Opium Wars

I had not come to China for health or pleasure, and that I should remain at my post as long as I could sell a yard of cloth or buy a pound of tea.

--RB Forbes to Capt. C Elliot, British Superintendent of Trade in refusing to leave Canton during the 1st Opium War

Relations between the West and the China has always been strained. There was little from the West that the Chinese wished to buy and their emperor would only receive ambassadors as if they were tribute bearing vassals. Also in the highly structured Chinese social caste, merchants were very low and were not worthy of respect, let alone discourse at an official level. For many years dealings with Westerners were delegated to a few "Hong" merchants who paid for the "privilege" and had to vouchsafe their commercial dealings with the "white devils." High Commissioner Lin Tse-hsu came to Canton in 1839 with an order to "investigate the port affairs." The first edict against opium had come in 1729; another against smoking came in 1796. The trade had grown to 40,000 chests and growing by 1838. The novel, more soporific and addictive manner of smoking opium plus the encouragement of the trade by the British and others—for both economic and imperialistic motives—devastated all segments of Chinese society. Corruption and smuggling was rampant, creating apathy; and the opium trade was also draining China's treasury.

Comissioner Lin Tse-hsu c. 1850 anon.

Lin couldn't believe that opium was legal in Britain and wrote a letter to Queen Victoria to implore her aid in stopping the trade. He disrupted the local merchants and published new edicts against the use and importation of the drug. Lin demanded that all chests of opium be forfeit as contraband and all trading houses sign a bond, pledge to smuggle no more and become liable to Chinese law which included the death penalty. Through threats, a servant walkout, giant gongs that were rung all-night and other measures, Lin was able to collect over 20,000 chest of opium (about half of that year's Indian trade). Then under orders from the emperor, he destroyed it all.

This conflagration sparked the first Opium War, made huge profits for those firms that had held on to chests and left Russell & Company the only trading firm left open in Canton.

During that first Opium War, the Chief of Operations for Russell & Co. in Canton was Warren Delano, Jr., grandfather of Franklin Roosevelt. He was also the US vice-consul and once wrote home, "The High officers of the [Chinese] Government have not only connived at the trade, but the Governor and other officers of the province have bought the drug and have taken it from the stationed ships … in their own Government boats."

Wu Ping-chen or Howqua II, the leading "hong"

merchant—considered by some to be one of the

world's richest men at the time—was worth over

twenty-six million dollars in 1833.

The trading life started off rather spartan, but through the years many upscale amenities led to a pampered gentry lifestyle. Profits were huge and many fortunes were made. Warren Delano went home with one, lost it and then went back to China to get more. Russell Company partners included John Cleve Green, banker and railroad investor who made large donations to and was a trustee for Princeton; A. Abiel Low a shipbuilder, merchant and railroad owner who backed Columbia University; merchants Augustine Heard and Joseph Coolidge. Coolidge's son organized the United Fruit company, and his grandson, Archibald C. Coolidge, was a co-founder of the Council on Foreign Relations. Partner John M. Forbes "dominated the management" of the Chicago, Burlington and Quincey, with Charles Perkins as President. Other partners and captains included Joseph Taylor Gilman, William Henry King, John Alsop Griswold, Captain Lovett and Captain J. Prescott. Captain Prescott called on his friend and agent in Hong Kong F.T. Bush, Esq. frequently. Russell & Co. and Perkins & Co. families, relations and friends are well represented in the Order of Skull and Bones.

After the first Opium War, the port of Shanghai was opened up, with Russell & Co. as one of it first traders, and the Stars and Stripes was the first flag flown in the new concessions. In 1841 Russell & Company brought the first steam ship to the Chinese waters and continued to develop transportation routes—as long as opium made them profitable. They also were invoved with early railroad ventures in China.

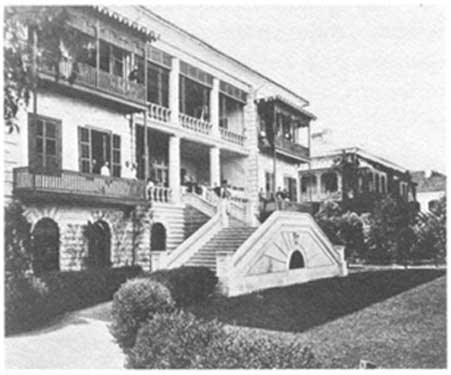

Russell & Co. Shanghai Headquarters c.1890

Spanish traders had joined with American and British traders in the early decades of the 1800s and Manila in the Philippines harbored several trading houses. These were used as offshore support and subterfuges in the opium smuggling dealings and "posturing."

The discovery of gold in California brought more dynamics, increased clipper ship activity and a renewed impetus for transcontinental railroads—which were financed a great deal by opium profits from investors in America, Britain and Scotland.

The second Opium War led to the legalization of opium in China in 1858 and the "country traders" began to lose their control. They were smugglers warehousing the "product" offshore and trying to control the flow—for maximum profits. Once the product was legalized the Chinese and Indian merchants started to take over the trade. Russell & Co. and others because of their role as smugglers had not developed a structure to sell opium in inner China. The Chinese brokers could now just order opium as any commodity and the trade was transferred to firms with strong ties at the producing base, India, and the consuming behemoth, China. Russell & Co. formed the Shanghai Steam Navigation Company and by 1874 they had 17 steamships—the largest fleet in Shanghai. Russell & Co. sold the Shanghai Steam Navigation Company to the China Merchant’s Steam Navigation Company in 1877 and the American share of Chinese shipping dropped by 80%. Russell & Co. is listed in some sources as failing in 1891 with British and German firms taken over their business. The Chinese Government an associate of Russell & Co. in the coast and ocean trade "lost heavily." According to some, the Russell & Co. successor in Shanghai was Shewan & Tomes.

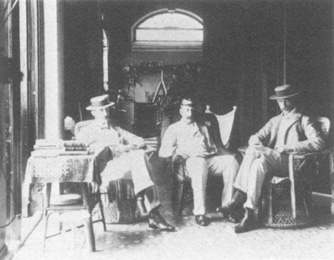

Charles A Tomes[r] and friends, Hong Kong(1896)

The legal opium import trade continued until the early 1920's when an Occidental moral backlash, official regulations and Chinese political turmoil put the trade in the hands of the Chinese government—and Chinese gangs. Out of the turbulence—many years later—came Nationalist Chinese leader Chaing Kai Shek. Some reasons for his success came from the backing he received from the Shanghai's narcotics trafficking Green Gang and his "political manipulation of the narcotics traffic, under the guise of an 'opium suppression campaign, "to finance both a political and an intelligence apparatus."

In the early part of twentieth century there were many changes in the opium trade. China and India reached an agreement for cessation of Indian opium imports. By 1920's opium had infiltrated every part of Chinese life, 90% of males in some provinces smoked, morphine was called "Jesus opium" because of its introduction by Western Missionaries as a cure for opium addiction. China was a country divided-up into many different political units with "control" ceded to Japan, America and various European nations.

A "prize" from the Spanish-American War, the US had taken control of the Philippines and soon declared opium illegal there. William H. Taft (S&B 1878) had a huge hand in the establishment of US narcotics laws. He exhorted Americans towards the formation of international "narcotics" control and prohibitions. There was also the formalization of an early relationship that Yale University had with China into the Yale-in-China program. Behind these movements one can discern influences of Bonesman such as Anson Phelps Stokes (S&B 1896) and others. Skull and Bones interest and participation in the Philippines is immense. More on these stories later.

China was importing massive amounts of heroin from Japan and was officially blaming the Japanese for its problem. Japan did use opiate production both for economic accumulation and as a political tool, especially in Manchuria. But the Chinese heroin trade was larger, by the late thirties over 85% percent of the world's heroin was coming from China headed towards Europe and the Americas. Chinese, Japanese, French Corsican, Arnold Rothestein’s Jewish-American, and Lucky Luciano's American-Sicilian crime syndicates were involved.

During WWII, Chiang was fighting both the Japanese and Communist and towards the end of the conflict in the opium dominated province of Yunnan an interesting group converge—the OSS, Chenault's Flying Tiger's and remnants of Chiang's Army, the KMT. Individuals included E. Howard Hunt, Lucien Conein, Mitch Werbel, Ray Clines, William Pawley, Paul Heilwell, Major John Singlaub and others.

Which leads us to some more interesting stories and—interesting Bonesmen.

A sneak peek:

to be continued . . .